|

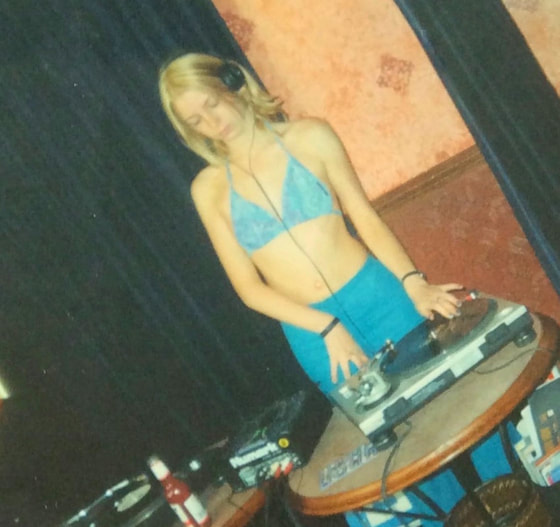

House music DJs will tell you playing to the crowd is all about the journey. The average set length is ninety minutes, like a feature film. In the same principle as filmmaking, you want the audience to have some kind of self-discovery. Anyone can stand up there and play two hours of solid hits (and believe me many do), but as with a documentary you want to subtly reveal the world of the story to the audience with visual indicators, suspenseful cuts, and cliff-hangers. The only way to do this of course without possessing some psychic ability is to be able to read the crowd in an instant. Acting on impulse is something I’m sure any documentarian can relate to. A DJ will consider and plan a set for the night but their interactions with the crowd can change this in a house beat (excuse the pun). A self-shooting filmmaker will turn up on location with a plan for the day, but who can predict human nature in any moment? The Retrospective Track I am one of those people whose parents would describe me as a cartoon character to their friends, ‘she came out of the womb dancing.’ As bizarre as this analogy has always sounded to me, music is one of the only constants in my life, a best friend offering me safety, escapism, opportunity, and passion. For me, a walk around the supermarket has a soundtrack whirling around in my mind which would be at home in the opening credits of a retro biopic about a struggling musician. Perhaps it was no surprise then to those who know me that my adult life would begin with a career in the music industry. Raised in a family of blues pianists and rock musicians maybe this is structured in my DNA, or maybe this has over time become culturally imprinted. Sweet sixteen for me was not shopping trips to the mall with friends sharing a strawberry milkshake, nope, sixteen for me was every weekend from noon until night hanging out in the cramped attic bedroom of a four-story run-down Victorian townhouse inhabited by several other aspiring DJs or broke musicians, depending on your stance, and a bottle of flat vodka and cola. For hours I waited patiently and listened intently until it was my turn to take to the decks and play the same two 12” vinyl tracks back and forth for an hour until those four-to-the-floor beats matched seamlessly, flowing one 1990’s house track into the next. A partially raised eyebrow from any one of those guys waiting in line was the subtle acknowledgement of my achievement, and also a definite hint to make way for the next future spinner. A DJ career followed, playing gigs across the UK house music landscape. Perhaps those anxious glances of acceptance across the smoke-filled attic at such a young age produced an inherent ability in me to be able to read a crowd, second-guessing their thoughts by the faintest of facial reactions, whilst also challenging my senses by having to simultaneously mix two pieces of music without missing a beat….This was fun for me by the way…..some of the best fun I’ve had in my life! The Remix Skip forward to today, and sure enough, as if imprinted in my DNA, the pattern restarts; Weekends for me in my forties are not meeting friends for coffee at the local delicatessen, nope, a Saturday for me at forty is driving the UK house music landscape, this time my record box replaced by my camera trolley, spending hours in haze filled night-time venues. One year into a fresh new career in filmmaking, again perhaps no surprise to my nearest and dearest, my portfolio to date is a range of music videos, music-themed fiction and most recently, a feature documentary about house music, which five months in I already see as one of the greatest achievements in my working life, a project that sixteen-year-old me would’ve seen as my dream job. The advice from my lecturers, peers and mentors so far has been consistent in guiding me toward the mantra of ‘create what you know.’ When the opportunity arose for me to self-produce and direct a film about some of my most loved house music artists, I felt I had once again found my thing. Ecstatically spellbound and slightly out of my depth but grateful for the faith in me the subjects and contributors have shown. The question of the hour though is; what is it that these established musicians have registered in me that has given them the faith to trust a brand-new documentary filmmaker, still studying at university with a very modest portfolio in telling their story? There is something embedded in my history, hidden in plain sight that is seemingly the most crucial and pertinent point in my becoming a more sensitised documentary filmmaker. The Crescendo If anyone asked me up until I started writing this blog, why make this film? I would’ve answered by explaining that my love for music and film and my creativity have powered my drive into two careers in the arts. I would’ve told you about how forming ideas and realising them for others to consume stories in the world of house music was everything to me, and I would’ve said something about pushing boundaries and expression…… I of course would’ve been right; valuable aspects of my career and lifestyle choices. My crescendo though, that little voice slowly building, those hidden skills that have elevated me as a documentary filmmaker in such quick succession have come not from my technical and artistic ability but a very personal and humanistic place. The magic formula in my journey to finding the story was crafted many years ago in that smoky little attic; Reading the crowd captures the essence of the story! The sensitivity I developed as a very young woman being watched intently whilst learning my craft, has embedded some little triggers into my psyche which allow me to instinctively make the right moves when filming live. This has allowed me to capture some of the most poignant moments in interviews, outrageous footage when filming crowds and celebratory moments of real life on film. My instinct kicks in just as it did when those eyebrows raised, and my body follows, moving the camera with a power from within that has very little to do with action or planning and more about reaction. If you are reading this as a filmmaker or a DJ, take some time to find the feeling inside of you that triggers this and what will follow is a genuine depiction of your style powered by a feeling of what the people in the world of the story or audience demands. This is so personal, leading back to that age-old advice of ‘creating what you know.’ May the results work towards giving you your unique voice and style. This, I am rapidly realising is as essential to me if not more so, as my technical know-how and creative ability. Take the time to feel the music, read the crowd. Author  Sarah Michelle Durrant is a Writer/Director/Producer and the sole owner of Glam Rock Films. Her current projects include music documentaries and videos for artists including K Klass, The Astras, The Institutes, Courthouse and DJ Seb Fontaine. She is currently in the development stage of adapting the novel 'Cola Boy' for the screen. contact: @sarahmichelleglamrock; [email protected]

0 Comments

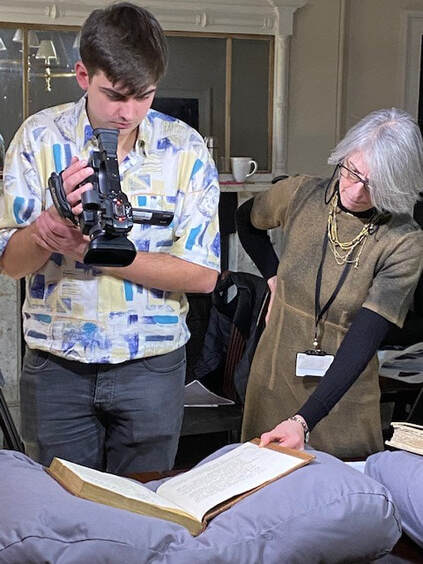

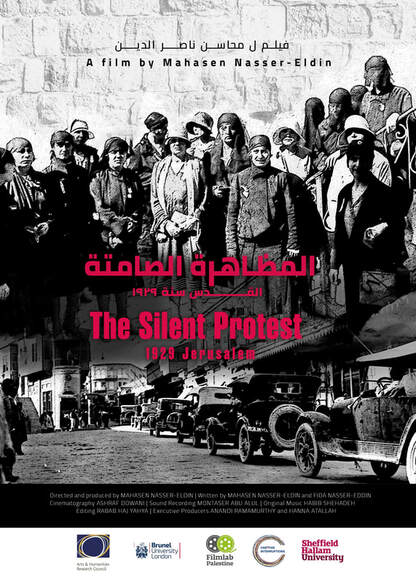

I've never considered myself a lucky person. I've had my fair share of opportunities but lucky? Nope……and yet. Standing on the beach at Wells Next The Sea, with the sun glaring down and a seal chilling on a sand dune before me, while I bossed (some call it directing apparently) a dynamic cinematographer and a production assistant around, I certainly felt a sense of luck. And yet….this situation arose from ‘opportunity’. I say opportunity purposefully and I mean opportunity not AN opportunity. Some given, some created and here lies the core of this blog: What to do with fantastic opportunities and where to find them. It's likely that the story of exactly how I came to be standing on a beach filming with a crew will give a better, more interesting account than anything else I could offer to help you understand about the power of opportunity. So here goes: I'm a student, a Film Studies student at DMU, currently coming to the end of my second year. Through my first year (and my first pandemic!) I quickly realised that I could get through uni without getting too involved. I could attend my classes and do my assignments and that would be that. I would work hard, get a first and go on to do an MA. But deep down that wasn’t what I wanted or expected for my university experience. I wanted to learn about film and watch films, yes, but I also wanted to be involved in the creation of film in all, and any way possible. So, without absolute opportunities handed to me on a plate, I looked for them. It wasn't until the beginning of the second year that I started a new module called ‘Professional Practice - Film Festivals' that I saw the perfect opportunity. I knew when I chose this module that this was the opportunity I craved. It had opportunity written all over it, even if this went above and beyond the needs of the module. A year of learning, planning, developing, and then running a film festival was just full of potential! So, I threw myself into it and looked for and created the opportunities I had been wanting. The module required us students to come up with an idea for a film festival which we would have to pitch to film professionals, peers and lecturers who would then vote on the one they thought would fit the brief best. Then the chosen idea would become a fully-fledged film festival. I am lucky enough to have a passion for history and in my spare time when I am not watching or involved in films, I am researching history, all parts of history in an attempt to broaden my knowledge, or at least write down where I found that knowledge online (to give me some credit I have a ton of books). Having previously written a piece about Leonardo da Vinci I was already aware of a document called the Codex Leicester - I knew it was historical, obviously, and had Leicester in the name, obviously, so it must be a good option, surely. The Codex Leicester is a manuscript written in around 1510 by Italian artist, scientist and utter genius Leonardo Da Vinci. Da Vinci is well known as a Renaissance painter with such works as The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa as well as The Vatruvian Man. He was born in Florence, Italy in 1452 and throughout his life had an unlimited desire for knowledge. As well as being a painter, he was a polymath, an engineer, an inventor and a theorist (to name a few). Quite simply the Codex Leicester was a book in which da Vinci had written about his theories in a type of coded handwriting. It was brought to England in 1717 by Mr Thomas Coke who just happened to also be the Earl of Leicester. Jump to 1994 and William Henry Gates III, aka Bill Gates, yes THE Bill Gates, purchased this book for over $30 million! Making it one of the most expensive books ever sold. Here we are with a link between Leicester, Leonard da Vinci and Bill Gates - it really was like something out of a film! Or certainly a film festival. And so I pitched my idea. And won - and yes, I did feel lucky at that point as there were some fantastic ideas from the other students too. So the Codex Leicester Film Festival was born and with it a ton of other opportunities. Although this was not part of the aims of the module, I saw another opportunity to create a short documentary about the Codex Leicester that could be screened at the film festival. I emailed everyone that had the slightest link to the Codex Leicester, including The British Library, a Leicester historian, the ancestral home of Thomas Coke and yes, Bill Gates. The Leicester historian emailed back (which I will talk about later) and so did the curator of manuscripts at the ancestral home of Thomas Coke, Holkham Hall in Norfolk. After a bit of negotiation, the curator at Holkham Hall agreed to an interview and for us to create a short film about Thomas Coke and his link to the Codex Leicester (they have a facsimile of the original at Holkham). I sent out an email to all film studies students asking for a cinematographer, editor and production assistant. The opportunities were growing not just for myself! So in late March on a beautiful sunny day, myself and a camera crew (all first year students at DMU) who themselves had recognised a great opportunity, set off for Norfolk (I say a beautiful sunny day but it was still pitch black when we left!). We spent 14 hours together filming the beach, the interior and exterior of Holkham Hall, the interview with the curator as well as the books linked to the Codex Leicester. It was an utterly wonderful experience and one I will never forget. We came back to Leicester exhausted but excited to hand all our hard work over to another, exceptionally talented first year student to edit. The turnaround time was 10 days (I’m still staggered at this) and although we will continue to edit and probably revisit for more filming, a version of the documentary was screened at the Codex Leicester Film Festival Celebration Event! Which was then seen by film professionals, students and lecturers and plans are being made for this film to go on to be shown at local venues next year. What an opportunity. But the legacy goes on. Not only did the documentary happen and those involved benefited greatly, but also a number of other opportunities are ongoing today. As for the Leicester historian, we are just about to start working on a different documentary about another manuscript called the Codex Leicestrensis that is actually in Leicester. It predates the da Vinci codex and I got to see the original at the records office. Without the new opportunity that I created from the one I was given, I would never have started what I’m working on now. The moral of the story: if you can - use, create and take all the opportunities that open up to you. You never know where it might lead. Author  Miranda Loveridge-Graham is a Film Studies Student at DMU. She is the owner of ManuScript Media as well as the Director of ManuScript Theatre Company. Miranda is currently the Head of Volunteers for the UK Asian Film Festival Leicester and is involved in a number of other projects. Contact [email protected] for further information. How is history relevant? How do we create visual representations of history that resonate with the present? How can archival film create de-colonised narratives that further our understanding of subaltern histories and experiences? As a documentary filmmaker and researcher engaging with colonial archives I have been reckoning with these enquiries as I create archival films and representations of Palestinian women pre Nakba Palestine (1948 Palestinian Catastrophe). I am interested in pursuing archival film as a way to revive meanings of the past within colonised societies where local narratives have been lost and abandoned by “dominant” histories. Archival film in that sense may capture representations of history that respond to local -on the ground- needs for cultural expressions that locate the “missing” in lost knowledge. It also has potential to lead reflections on how the past is constructed and represented with a relevant lens to present times. Archives are sites of memory and narrative in which states consolidate historical material in the form of documents and records, signifying their power to create and control knowledge and meaning about the past. Embedded in the politics of power, states compile, structure and categorise the archives to construct nationhood, shaping collective memory, national identity and history. Jacques Derrida writes in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, there is “no power without the control of the archives, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and access to the archive, its constitution and its interpretation” (Derrida, 4). In practice, the archive is never neutral or objective. The archive often constitutes a record of a nation’s victory as well as brutality over another. Access to archival material and information is not always possible, particularly when search inquiries reach the cracks in the archive and undermine the politics and historical narrative of the state. This is no more true than when the researcher is searching the archive for subaltern histories. The archive in this context becomes a site of ongoing contestation where the researcher needs to be persistently critical of the exclusions and absences that the archive hold against the subaltern. Moreover, to search for subaltern history entails understanding the semantics and logic of the archive and its narrative, in order to locate the missing links. Derrida declares that the archives “store, accumulate, capitalize, stock a quasi-infinity of layers, of archival strata ... are at once superimposed, overprinted, and enveloped in each other. To read… requires working on substrates or under surfaces, old or new skins” (Derrida, 22). Thus, the task of the researcher in this condition becomes subversive and aims at excavating additional layers of knowledge and meaning generated through her search in the archive. Searching the archives poses tremendous challenges to the researcher of the history of Palestine, let alone to the researcher working on the history of Palestinian women. A researcher would have to search in the scattered archives in historic Palestine (present day Israel) and the various localities of the Palestinian diaspora as well as in the UK, the US and other countries, to collect fragments of private and public records. On the other hand, the state of Palestinian national archive is as tenuous as the Palestinian State itself- both are non-existent. The researcher doing archival search on Palestine would have to visit Israeli archives. State, military and national Israeli archives hold overwhelming numbers of civil, military and security records that date to British colonial rule in Palestine. These archives are not always accessible and they hold imbedded representations of erasures toward Palestinian history and its people. In my tackling of these challenges and in my process of locating the “missing” knowledge related to Palestinian women’s lives before 1948, Walter Benjamin’s “Berlin Childhood Around 1900” became an inspiration for me. Benjamin eulogising a place and time gone by declares: “I, however, had something else in mind: not to retain the new but to renew the old. And to renew the old – in such a way that I myself, the newcomer, would make what was old my own- was the task of the collection that filled my drawer” (Benjamin, 156). Throughout the making of “The Silent Protest: 1929 Jerusalem”, the film I am presenting here, Benjamin’s words accompanied me. This film is a short documentary that follows a day in the life of the Palestinian women’s movement in 1929 under British mandate. The film creates a narrative from memoirs, personal letters, photographs, official records, news archives and oral history accounts, exploring the construction of Palestinian women’s history through film and the meanings of these constructs and representations in present time. My archival search to make “The Silent Protest: 1929 Jerusalem” stems from my documentary film “Restored Pictures” about Karimeh Abbud (1893-1940), the first Palestinian female photographer in early 20th century Palestine. The personality of Karimeh Abbud led me to the feminist work of Matiel Moghannam, one of the women organisers of the Palestinian women’s movement in 1929. Moghannam in 1937 published her book The Arab Woman and the Palestine Problem through Hyperion Press in Westport, Connecticut. In her book she documents the inauguration of the women’s movement in 1929. She informs her readers that on the day of the inauguration of the movement 200 woman participants endorsed the cancellation of the Balfour declaration and they protested British policy and rule against the Palestinian population in the country. Moreover, Moghannam informs us that the women organisers formed protest and media committees for addressing the organisation of protests and addressing media and press with regards to the political conditions in the country. The inauguration event concluded with a delegation of women sent to meet the British High Commissioner, John Chancellor and to present him with a statement including a number of demands that highlighted the extreme and inequitable treatment of Palestinians by the British in Palestine. This delegation of women then rejoined the rest of the inauguration event participants on a protest of cars that paraded the streets of Jerusalem calling against British mandate policy and rule in the country. The women delivered statements to foreign embassies and emissaries in Jerusalem. Women worked within the national framework and created a movement independent of nationalist male structures. I believe the dismal conditions of global and local politics we are witnessing today not only trigger us to think of how our struggles and grievances as women are overlapping, but also of the urgent task of looking into the past through a lens of continuity in experience. Contemporary feminists in Palestine and elsewhere juggle various identities and balance affiliations based on class, religion, race and sexuality, very much similar to “early modern” feminists who also negotiated similar tensions while shaping their feminisms. Through my film works I wish to deepen our understanding of how social and political contexts shape women’s lives, historically and in present times. I am interested in the construction of imaginaries through film and in understanding practices of social justice and feminist liberation. Works Cited Benjamin, Walter, Berlin Childhood around 1900, trans. Howard Eiland. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2006. Darrida, Jacques. The Archive Fever. A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz. 1995; repr. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998. AuthorMahasen Nasser-Eldin is PhD student at De Montfort University in the UK, pursuing practice-based research in archival film. She is a filmmaker whose films tell stories of resistance and resilience, crafting carefully researched and scripted narratives that restore new life to forgotten figures and celebrate those on the margins of society. Mahasen’s research focuses on the re/use of audio and visual archives in the writing of historical narratives through film. Her study is interdisciplinary and draws on different bodies of literature relating to archive practice, subaltern histories, transnational feminism and subjectivity. I discovered filmmaking studying at DMU. It was fun, but I didn’t imagine it as a career. Until I asked a friend about her ambitions: she told me she wanted to be a filmmaker, I thought it was the most ridiculous thing I had ever heard, like she wanted to be an astronaut or a formula one driver… on second thoughts, if she can be a filmmaker, I can definitely be a filmmaker. That’s how it began, and 24 years later, I’ve just been nominated for a Royal Television Society Award for Best Documentary. My films have played at international film festivals, independent cinemas, and on TV in multiple countries. So how did I get here? I like to imagine that I achieved my ambitions through hard work, determination, and a peppering of talent, and to some extent this is true, but looking back I can see that I was certainly given a helping hand along the way. Inspiration, incubation, acceleration. It always starts with inspiration: The filmmakers who went before me. Shane Meadows (This is England) played a big part in my development. I only met him a couple of times in passing, but my very first job in the film industry: runner at Intermedia Film and Video in Nottingham, was actually Meadow’s first job ten years before me. I observed his career from a distance, and genuinely felt like I was following in his footsteps (to some extent). And then I encountered the inimitable documentary filmmaker Mark Isaacs at an event called Doc Day at Broadway Cinema in Nottingham. The way he spoke about documentary filmmaking after a screening of his debut film 'Lift' (2001) totally inspired me. Now I find myself working with the same distributor as Mark: Verve Pictures. Incubation – in case you’re unfamiliar with this term, or you think I’m talking about eggs, premature babies, or diseases; the business incubator is a place where new enterprises are encouraged to grow. The word wasn’t in common parlance in 2004 when I received my first TV commission from ITV: 'Deliver Us From Evil'. It was part of a new talent scheme, and in many ways this was an incubation of my craft as a filmmaker. It gave me the opportunity to learn and grow in a professional environment. Shortly after this I established my production company Intrepid Media, and set up my own office at LCB Depot: a supportive environment in which many of the best creative digital companies in Leicester have established and grown. 16 years later I’m still based at LCB Depot (www.lcbdepot.co.uk), I love it here. Acceleration happened for me on a training programme: Fast Track to Features, run by Sheffield DocFest. It was all about helping producers and directors who were determined to make their first feature documentary. Since then (2013) I’ve produced two features and I’m well into production on my third. I couldn’t have done this without this input designed by Charlie Phillips and the DocFest team. Eventually you get to a point in your career when you’re asked to give back and help others to progress. So, I’m delighted to be working for Phoenix at the moment, I’m still a filmmaker most of the time, but for the next year or so I will be managing Phoenix’s REAL Initiative. The vision of REAL Initiative is to work towards establishing Leicester as a regional centre for documentary filmmaking and non-fiction digital art. And we are delighted that this vision is supported by our funders the European Regional Development Fund, Midlands Engine, and Arts Council England. 'Over the next 18 months Phoenix will be offering support to ambitious individuals and enterprises (based in Leicestershire) wanting to start-up or grow businesses in film and digital art, particularly those interested in documentary. And when we say documentary we mean this in the broadest possible terms. I make long form documentary films for TV and cinema, a form that has been around for a hundred years. I have a film poster in my office for Dziga Vertov’s seminal 'Man With A Movie Camera' from 1929. And really the work I produce adds very little innovation to the form (apart from sound). But of course it’s 2022 and immersive digital technologies offer new and innovative ways to progress the form. So, whether you’re a traditional filmmaker, a technologist or an artist, or something in-between, then hopefully there could be a place for you in REAL Initiative. REAL Initiative is offering Inspiration, Incubation and Acceleration. You can find details of this FREE programme at https://realinitiative.phoenix.org.uk. Applications are open, apply before April 8th 2022.  Nick Hamer is a Leicester based documentary filmmaker, director, camera operator and editor. His work has been screened by major broadcasters, international film festivals and independent cinemas. Nick established his production company Intrepid Media in 2004 to produce high quality factual films and has directed successful shoots for high profile organisations all over the world. His feature documentary OUTSIDE THE CITY about the monks of Mount St Bernard Abbey follows a community of 25 men, more than half of them over 80 years old, who are opening the first Trappist brewery in the UK. OUTSIDE THE CITY was broadcast by BBC FOUR as Brotherhood: The Inner Life of Monks. In December 2021 DMU celebrated Disability History Month with an exciting and inclusive line-up of virtual and in-person events. As part of the programme, The DocHub hosted a screening of the documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (2020), directed by a former camper, Jim LeBrecht, and Nicole Newnham. We commissioned DMU’s Film Reviewing Society to submit a review of the documentary with the winning entry by Kick de Brabander featured as The DocHub’s inaugural blog post. Dear ‘Normal’ People An American summer camp away from society where minorities are treated equal. Minority and majority are binary opposites. When relating these terms to humans, it makes us all divided, black and white, colourless. Every one of us is different and should be treated equally; being normal just does not exist. The definition of ‘normal’ differs depending on the person you ask. This opposition of ‘not normal’ and ‘normal’ is placed unknowingly in our minds by societal standards. We are told by the police that the colour of your skin may mean that you are more dangerous, by society that we should always strive for more money, and by the world that it is an imposition to design cities that are accessible for wheelchairs. If this made you mad, good. Anger is what helps people stand up to unfairness. Of course, when we are told about these societal discriminations we do not always listen, but doing nothing is not enough. If anger ignites our fuses, getting together is what starts a real fire. One such fire started when the largest group of minorities in America came together as kids for a fun summer camp, run by hippies in 1971. The documentary that splendidly portrayed the rage of these kids is Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (2020). Written, directed, and produced by Nicole Newnham and James LeBrecht, this film is an excellent depiction of these emotions through the perspective of people with disabilities. Using present day interviews with people reminiscing over Camp Jened; the summer camp where they felt most at home, whilst the narrative takes us back in time through old footage that was made at the camp in 1971 and news reports on later protests in the ‘90s. When the teens first arrived at the camp, you could feel how uncomfortable these kids were and talking about their lives on the camera you find out why they would feel this way. On the old footage they told their stories and how they felt in a society which treated them different from everyone else. This was true because the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which prohibits discrimination based on disabilities, was not approved till 1990. Thus, before this there was a difference in how ‘normal’ people acted in front of people with disabilities. The ‘70s were harsh times, especially for kids with disabilities but funnily enough when they arrived at that camp everything switched. At this camp, they could be whoever they wanted to be without anything holding them back. They played games that they had not been allowed to play in mainstream schools, such as baseball and football. At Camp Jened they were treated like kids because that is what they were. Aside from the older footage, what also easily takes you back to the ‘70s is the music. With the opening credits playing For What's It Worth by Buffalo Springfield, it immediately puts you in that late ‘60s rock ambience. There was also another great moment with the song from Richard O'Brien, Sweet Transvestite. Campers were invited to a Halloween party, where they could dress up and get drunk. A stage was set up and an announcer called up Steven Hofmann, the song started playing and we see Steven dressed up as a woman, stripping off his clothes with a lot of pride. It is especially great when his quote is put beside him "If you're a handicapped person, and you happen to have a passive nature about you, you're really screwed." In contrast to the fun Camp Jened, a state hospital known as Willowbrook is shown through a news report. This is absolutely horrifying. For fifty disabled children there was one attendant, children were laying on the floor covered with their own excrement, almost starving because they could not feed themselves. It makes you wonder how many more horrible hospitals like Willowbrook are out there. These kids were treated as less than human. It is something you only want to see in horror films, because in reality it is too shocking. This documentary covers a serious subject whilst having some fun highlights and emotional moments. Crip Camp not only educates us about past problems, but also persuades us to be better in future. After ADA was declared in the ‘90s, disabled people celebrated it but weren't wholly satisfied. The ADA was only one step closer to a just world, however what these activists had to tackle now was the attitudes of non-disabled people. The prejudices of society must change because, in the words of Denise Sherer Jacobson, "you can pass a law, but until you change society's attitudes, that law won't mean much." This is what the film is trying to do, showing that humans with disabilities are humans too. Everyone really ought to see Crip Camp. It is an amazing story told by amazing people. We can all learn from it and, if we spread the message that it has and stop normalising those binary terms, then maybe we can all start living a 'normal' life. If communities of people are angry, we should take on that job to find out the reason for that unhappiness. If we understand it then we can help make the necessary change. Anger is a good thing, unrighteousness is not. So, let us build some fires with that anger and warm more people up. Changing their attitudes will change society's and make it a better place for us all. by Kick de Brabander  I was born in Venezuela (Caracas), raised on an Island in the Caribbean (Curaçao) and moved to the Netherlands to study acting. However, my love for films and the passion for creating stories was much greater than acting, and for that reason I moved to Leicester to study Film at De Montfort University. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed